World Soil Day: Digging plant conservation

-

Region

Africa -

Programme

Global Trees Campaign -

Workstream

Saving Plants -

Topic

Tree Conservation -

Type

Blog -

Source

BGCI

On this World Soil Day, it’s a great time to remember that the soil is incredibly important to plants for their survival and growth. It is the source of the water needed to photosynthesise carbohydrates and the nutrients needed to build cells for growth and reproduction.

Soil composition affects both water and nutrient availability. Sandy soils are fast draining on the one hand, whilst clay soils, in contrast, hold onto water. When water is able to flow through the soil easily, it transports ionised nutrients, increasing soil acidity. Ultimately, variation in soil type creates an assortment of conditions that plants have evolved to survive. For plants that become more specialised, this can lead to restrictions on the availability of the niche they can endure.

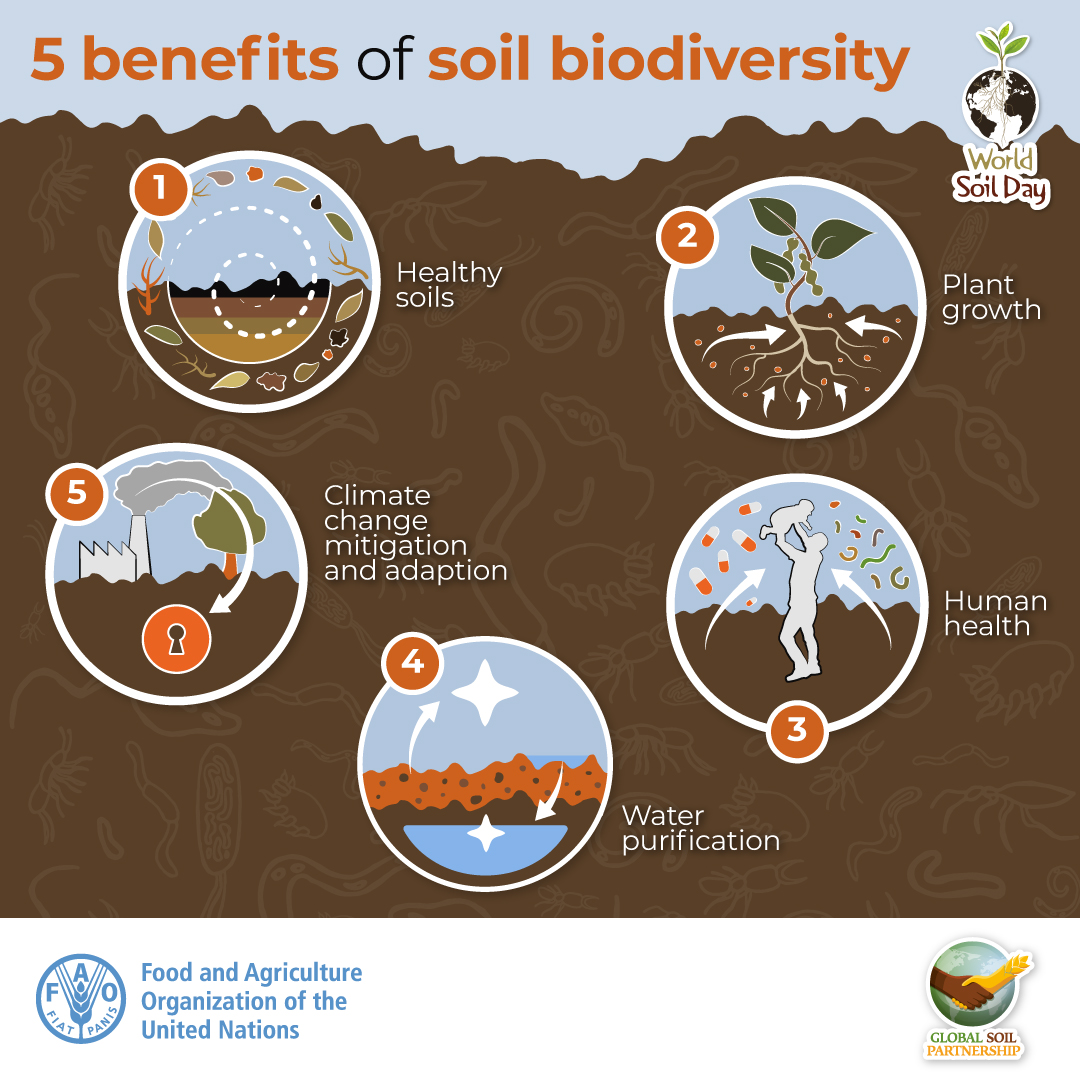

That is not the full story however. All soils have large and active communities of life forms within them, which also vary with soil composition. These include bacteria, fungi, worms and insects, all of which add to the complexity of an ecosystem and are key to soil health. Their abundances can vary with soil texture, nutrients, moisture levels, and individual plant species, whilst their functions can be beneficial or antagonistic to plant species’ growth and the ecosystem structure more generally.

Mycorrhizal fungi

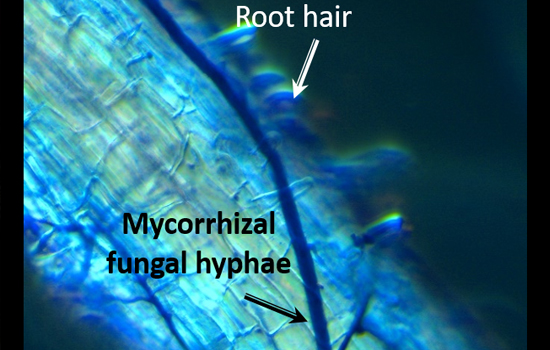

The rhizosphere microbiome is home to a diversity of fungi that affect nutrient acquisition in plants. Of these, the symbiosis between soil fungi and plants’ roots is one of the most widespread and ecologically important in terrestrial ecosystems. These provide their host plant with water and nutrients (like nitrogen and phosphorus) in exchange for carbohydrates. Mycorrhizal hyphae (fine root-like filaments) can even connect the roots of neighbouring plants for a wider exchange carbon, nutrients and water.

Although mycorrhizae are generally unified in their resource acquisition, the symbiosis with plants can be split into several distinct types, e.g. arbuscular-, ecto-, ericoid-, and arbutoid mycorrhizal fungi. These are based on the taxonomic identity of the fungus, their morphology within the root (e.g. entering root cells or surrounding them), the identity of the plant host, and their evolutionary origin.

Mulanje cedar conservation: from the ground up

For individual plant species, understanding their soil requirements and mycorrhizal partnerships can be quite complicated, as we have learnt through research carried out on the Mulanje cedar (Widdringtonia whitei) in a Darwin Initiative-funded project. The tree is a slow-growing gymnosperm, only found naturally on Mount Mulanje in southern Malawi. It is Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List because of overharvesting for its valuable wood; increased fire use on the mountain, reducing regeneration; and the species’ inherent long generation time.

Soil ecologist Louise Egerton-Warburton (Chicago Botanic Garden) and soil scientist Innocent Taulo (Forestry Research Institute of Malawi – FRIM) have shown that the natural soil conditions in which Mulanje cedars grow is highly acidic, with very low nitrogen availability and high organic matter content.

Mulanje cedar’s fungal complexity

Louise has also shown, through DNA analysis, the beneficial relationships formed with mycorrhizal fungal groups. This initially focused on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, widespread plant mutualists often found in other plants of the Mulanje cedar family, the Cupressaceae. Resource exchange occurs within root cells in specialized structures called arbuscules to typically increase water, mineral nitrogen and phosphorus uptake.

However, recent analysis has shown that the tree may form beneficial relationships with not just one group of mycorrhizal fungi, but three! This is unusual but has also been shown in the giant Californian or coastal redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) in the US – a Cupressaceae species, too.

The other two groups are ectomycorrhizal and ericoid mycorrhizal fungi. Ectomycorrhizal fungi are primarily associated with trees and mining leaf litter for organic nitrogen and phosphorus. Ericoid mycorrhizal species tend to be associated with members of the Ericaceae family. Interestingly, the low nutrient, acidic soils, especially those with accumulations of organic matter, often favour plants with these mycorrhizae because of their capacity for organic nutrient capture.

These associations may give the Mulanje cedar trees a regeneration niche advantage on parts of the mountain so that they became the dominant tree species, despite being slow growing. The flexibility in its fungi associations may link the plants to a variety of surrounding tree and shrub species to share resources through the hyphal networks. This flexibility would also give seedlings a greater chance to receive benefits through these shared mycorrhizal connections during establishment, wherever they land.

Restoration of the Mulanje cedar

The Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust (MMCT), FRIM, the Ecological Restoration Alliance of Botanic Gardens and BGCI have been collaborating to restore the Mulanje cedar. Hundreds of thousands of seedlings have been propagated and planted back on the Mount Mulanje. However, the team has noted leaf browning and die off after planting, even happening years later. With seed sources remaining in only two other sites in Malawi, every planted individual is a valuable commodity to the species’ future survival. We set out to improve the situation.

Armed with new information about the Mulanje cedar’s mycorrhizal requirements, we are establishing trials on the mountain to test protocols to improve the growth and survival of planted trees. These trials will investigate the effect of planting Mulanje cedar seedlings next to companion plant species growing naturally on the mountain. They will be positioned next to plants from families with potential mycorrhizal benefits (Ericaceae, Fabaceae, Asteraceae), plants of other families that are not expected to be beneficial or as controls, planted alone.

Our overarching objective is to identify better ways to plant Mulanje cedar seedlings back into their natural environment, helping to secure its survival on Mount Mulanje for future generations. The soil biodiversity might be vitally important to this, worth celebrating on this the 7th World Soil day.

* This article has been co-authored by Alex Hudson (BGCI) and Louise Egerton-Warburton (Chicago Botanic Garden)

Written by Alex Hudson for GTC. Alex is managing plant conservation projects in Africa (Malawi and Uganda) and the Indian oceans (Mauritius and Rodrigues). He is interested in ethnobotany and the interactions between conservation and development at the local level.

Become a Member

Be part of the largest network of botanic gardens and plant conservation experts in the world by joining BGCI today!

Support BGCI

You can support our plant conservation efforts by sponsoring membership for small botanic gardens, contributing to the Global Botanic Garden Fund, and more!